ADAD-IBNI SHIFTED UNEASILY on his cushion, eyeing the fig he held in his hand. The chief seer had taken two or three nibbles from the ripe fruit, and the sour look on his face had nothing to do with its taste.

Furtively he glanced up at the stern, pacing figure of Nabu-Naid, carefully composing his response to what the emperor had just proposed. “Everyone knows of my king’s deep devotion to Lord Sin,” he began, before wincing inwardly. Already he sounded too accusative. He started again. “No one has a greater appreciation than myself of the importance of reverence to the Moon Lord. But … my king well knows that the priests of Esagila would evince a certain … ”—he groped delicately for a word—“reserve … toward such an ambitious project as my lord proposes, unless it were directed toward the benefit of Marduk. Especially now—” Realizing he had said two words too many, the mage hushed.

Nabu-Naid stared hard at the bald-pated old man. “Perhaps you wished to say, ‘Especially now that the unpopular work in Haran is just completed’?”

The silence crackled with hostility in the morning-lit chamber until Adad-ibni could tolerate it no longer. “Surely my king realizes,” he said, squirming, “that by correcting the unfortunate state of affairs in Haran, he unavoidably attracted the attentions of certain malcontents seeking an excuse for the poor harvests.”

The emperor sneered at his chief mage, shaking his head in wry amusement. “How hard it is for you to say what you mean, Adad-ibni,” he smirked. “You of all people I would expect to appreciate my attentions to the temple, guarded so long and faithfully by my recently deceased mother.” Adad-ibni bowed low in respectful genuflection at the mention of the emperor’s ancient matron. She had lived so long that some half-thought her bewitched, and she finally died at the unimagined, toothless age of one hundred and four years. Her son had seen to it that her funeral was well attended and lavishly carried out.

“My king knows I hold the utmost respect for his revered mother,” said the mage. Hidden in his robes, his fingers made the sign against the evil eye.

“What you say in the silences between your many words,” huffed Nabu-Naid, turning his back upon the seer, “is that you doubt the priests of Marduk will permit, without severe compulsion, the construction of a proper temple to Lord Sin within the walls of Babylon.” Over his shoulder, the emperor turned a beetle-black eye upon the huddled, cringing form of the chief mage. “And we must not greatly discomfit the priests of the cherished Marduk, must we?”

The sarcastic tone of the emperor’s words frightened the mage almost as much as his anger. One should not trifle with the gods, he thought. Of course, he could not verbalize such a direct reprimand to his royal sponsor. With his habitual obliqueness, he observed quietly, “My king should also consider the sizeable resources controlled by the priests of Esagila. Without their agreement to contribute to the project—”

“The scoundrels!” Nabu-Naid snorted. “They take a man’s goats in security for a pledge, and when he can’t pay them twice the worth of the flock, they keep the whole mangy lot! There are scores of temples in this city, my city,” raged the petulant  king, “not to mention the hundreds of shrines and altars, but does Lord Sin, the Ancient One, have a house in which his name can be venerated?”

king, “not to mention the hundreds of shrines and altars, but does Lord Sin, the Ancient One, have a house in which his name can be venerated?”

Angrily he paced to the other end of the chamber, then whirled about to add, “Don’t think I’ve forgotten, seer: The house of Marduk gave money and materials for the building of that ridiculous edifice to Nabu in Borsip, but do you think they’d donate as much as a strip of copper if they thought Lord Sin might be so honored? Ha!” Again the emperor turned his back on the mage.

Under his breath, the mage quoted, “Nabu is the Son of Marduk, and the reflection of his glory.” This fixation of the emperor’s is ill-omened, he pondered miserably. But how can I tell him so? Aloud he said, “Perhaps my king should sojourn outside the walls of this city to refresh his mind—to pray to the gods and permit himself time to make a judicious disposition of this delicate matter.”

Nabu-Naid, toying distractedly with the amulet about his neck, suddenly halted, staring thoughtfully at his chief diviner. The wisp of an idea had wafted its way to him. With his eyes squinted in speculation, he began smiling. “Perhaps you are correct, Lord Adad-ibni.” A look of wicked relish crawled across the ruler’s face.

The mage could not fathom what was taking form in the corridors of his sovereign’s skull, but he suspected it could not be anything overly pleasant.

“Perhaps a tour abroad is precisely what I need,” grinned the king, rubbing his hands together. “Since you mention it, good mage, there are some ruins in Teima, in the far reaches of the Arabah, which I have wished to examine for some time. I understand they have many ancient inscriptions there, preserved in the dry sands of the region. I believe this is an excellent opportunity to pursue my passion for antiquities.”

The mage, apprehension clogging his chest, calculated furiously in his mind. Teima! The city lay leagues to the west, across huge stretches of desert not quickly traversed. It was already the middle of the month of Adar—the New Year Festival was only weeks away. Without the king’s presence in the capital, the festival could not take place. Gasping with dismay, the mage pleaded, “My lord! You cannot possibly travel to Teima and return in time for—”

“The festival, my lord mage?” An evil chuckle hissed from between the aging monarch’s dry lips. “You may well be right!”

“AND SO, MY BELOVED SUBJECTS,” announced the emperor to the silent, stunned courtiers, “I shall depart on the morrow for Teima. While I sojourn away from my beloved city, I leave my son, Belshazzar”—the emperor clapped a hand on the shoulder of the loutish, smirking crown prince—“to act as steward for the kingdom.

“I charge you all,” he concluded, “to obey him as you would me … ”

STANDING ON THE WALL of Sardis, the Lydian guard leaned back while drawing a draught of water. Suddenly the helmet slipped from his head, clattering over the edge of the battlements and finally coming to rest among the rocks below the citadel. Cursing under his breath, the sentry peered carefully about in the dusky light. No one watching—good. Gingerly he mounted to the top of the wall, then edged along the narrow shelf outside the battlements, more than a little mindful of the sheer drop yawning at his feet.

Reaching the corner where two walls joined, he climbed cautiously down to the rocks below the wall. This corner, known to few even among the city’s guards, was the only place one could descend to the ground in a relatively easy manner. Again looking about to see that he was alone, he made his way over to where his dented bronze helmet lay among the boulders near the base of the wall. Shaking his head in disgust, he strapped the headpiece to his belt and turned about to retrace his climb up the seemingly sheer wall.

Unseen by the Lydian sentry, two Persian spies slinked away from their observation post. When they were out of sight of the walls of Sardis, they trotted quickly toward the camp of Kurash. Their lord would be pleased with the news they brought this day.

KURASH CHUCKLED MERRILY, shaking his head in amazement. Rising from his couch, he said, “Scribe! Fetch me two bags containing a tenth-shekel of gold apiece.” Grinning at the wide-eyed spies, he continued, “I would reward the keen vision and quick minds of these two.”

For months the army of Medes and Persians had been encamped against Sardis, the glittering, seemingly impregnable capital of Croesus and his Lydians. Having won acclamation as king in Ecbatana, Kurash had quickly moved to quash Croesus’ incipient attempt at a land-grab in Cappadocia and Armenia to the north. The fantastically rich Croesus had thought to take advantage of the tumult in Medea to carve out a larger territory beyond his former eastern border.

But the Lydian gambit was doomed to failure. Kurash, at the head of a reborn Medo-Persian host, had swiftly routed the effete, well-groomed forces of the gold-king. Now Croesus and his minions were holed up in the citadel of Sardis, set on a rocky ridge behind walls that had, until this moment, been invulnerable.

“Boy, fetch me Commander Gobhruz,” Kurash ordered. The page scampered away. “Tonight, my fine fellows,” the king of Medea and Persia said, still smiling at the two newly rich reconnaissance men, “you shall escort the general to the place you found. We shall determine how many men, and in how quick a fashion, we can place inside the walls of Sardis. “And tomorrow,” he continued, more to himself than to the men, “we shall see who is the richest king in Lydia.”

BABYLON WAS NOT A HAPPY PLACE. The seasons ground inexorably along, the month of Nisan approached—and still no word came from Teima, the remote desert town to which the king had hastened. For yet another year it appeared the New Year Festival would not be celebrated.

Aside from the ominous prophecies of pestilence and disaster from the soothsayers and diviners, the city’s merchants and tradesmen grumbled about more prosaic matters: of lost trade and unsold goods, of profits vanished without the joyous excesses engendered by the rebirth and homecoming of Marduk. The temple prostitutes—and, for that matter, the freelance whores—were as unhappy as the others about the loss of commerce resulting from the emperor’s frustrating absence.

In Esagila, far darker mutterings could be heard. Throughout the temple complex, the emperor’s thinly disguised attempt at coercion caused the priests of Marduk to gnash their teeth in anger and pray unceasingly to the King of Heaven to bring down this rebellious and obstinate fool who had abandoned his people, leaving his surly and caustic son behind to pollute the palace with his ungracious presence.

But if Belshazzar was a boor, he was no simpleton. The prince-regent brutally intimidated his father’s opponents. He was unblinking in his use of the military, which he wielded with the iron grip of an absolute commander. Only a month ago, as the population watched aghast, he had marched a squadron of infantry into the very sanctuary of Ishtar, the heavy-breasted Lady of Uruk, and dragged out a priest known to be an open critic of Nabu-Naid. The man was hauled into the midst of crowded Aibur Shabu, where he was disemboweled and his corpse dumped unceremoniously into the Zababa Canal. Tactics such as this had had their effect; though extremely unpopular, the reign in absentia of Nabu-Naid was secure.

But if Belshazzar was a boor, he was no simpleton. The prince-regent brutally intimidated his father’s opponents. He was unblinking in his use of the military, which he wielded with the iron grip of an absolute commander. Only a month ago, as the population watched aghast, he had marched a squadron of infantry into the very sanctuary of Ishtar, the heavy-breasted Lady of Uruk, and dragged out a priest known to be an open critic of Nabu-Naid. The man was hauled into the midst of crowded Aibur Shabu, where he was disemboweled and his corpse dumped unceremoniously into the Zababa Canal. Tactics such as this had had their effect; though extremely unpopular, the reign in absentia of Nabu-Naid was secure.

The Jews of Babylon proceeded on their way, outside the mainstream of Babylonian custom and practice, yet unmolested. Their teachers and scholars read to them from the writings of their prophets and exhorted them from the pages of their ancient Law. They continued a process of coalescence around the adamant, unremitting core of their Unnamed One and His stone-hard, profound injunctions: Thou shalt have no other gods before Me; thou shalt not take My Name in vain; thou shalt keep My shabbat …

DANIEL GLANCED UP from his reading of the scroll, squinting his eyes and rubbing them with his fingertips. The oil lamp burned low, and the inked letters on the parchment had begun to flicker and waver before his vision with every dip and tremor of the unsteady flame. It was time to rest.

He rose, rewrapped the scroll, and placed it carefully beside the others on his reading table. Remembering the hard, worn face of Ezekiel, its author, he stroked the vellum sheath of the yellowing document, copied in the long-dead prophet’s own hand. He turned toward his couch.

Beyond mere fatigue and the lateness of the hour, he felt the weariness of his years pressing upon him. For almost fifty years he had been in or near the royal court of Babylon. The drain of the constant vigilance needed to navigate safely through the subtle feuds of opposing factions and personalities, the relentless responsibility of administering the endlessly mutable policies of the emperor and the prince-regent, the shifting, slippery surfaces of uncontrollable events, and the solicitous concern for protection and maintenance of the Chosen, his brethren—all these clamored incessantly for his attention. Added to them was his overarching, lifelong sense of being a foreigner in this city that, though almost the only dwelling place he had ever known, could never be home. Such cares and burdens caused each of his years to weigh heavily upon him just now, each of the sixty years of his life tugging at him with a nagging insistence.

“Sovereign Lord,” he prayed, his face buried in the scented linens of his bed, “I am so tired. Grant me the rest that is beyond sleep, beyond waking. Grant me the ease of soul that I crave; grant release, and quiet … ” Unable to frame within himself the words to express his longing, he found himself remembering Mishael’s lament by the tomb of old Caleb. In  some ways he could almost crave the quiet, the stillness of that final couch. An end to striving. A state when worry, care—the arduous necessity of being—was ended.

some ways he could almost crave the quiet, the stillness of that final couch. An end to striving. A state when worry, care—the arduous necessity of being—was ended.

“O my God,” he continued, “Your ways are too high for me. Your will is above the highest heavens, and I am but a weak and weary old man. Once I tasted the dizzying wine of Your choosing, but now I have only the tastelessness of old age. Twice I felt my tongue ablaze with the imperatives of Your message, but now my throat is parched by the aridity of the years. And thrice I was blinded by the brilliance of Your visions, but now I witness only the gathering of darkness. O Lord of Abraham,” he moaned fervently, “give me peace at last. Let me finally rest and be quiet.”

Falling on his couch still fully clothed, he tumbled into the deathlike darkness of an exhaustion far beyond the physical; it was weariness of the soul that claimed Daniel, and his breath came so slowly that each might be his last.

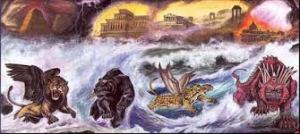

He stood on the shore of a vast and mighty sea. Feeling a cold, foreboding tendril of air moving against his cheek, he looked far out over the restless waters of the deep. A dark bank of clouds roiled along the flat plane of the horizon, pulling within itself, mounting higher and higher, as if gathering like a black panther for a vicious spring. Then a breeze from behind caused him to spin about in alarm. At his back, a huge cloud-beast coiled for the attack. Then he looked around, and on every horizon, all about the huge circle of the earth, the winds of creation were gathering for the onslaught.

Four huge maelstroms of the heavens rushed forward at once, smiting the sea and casting up waves as high as mountains. As he watched, terrified for his life, four hideous beasts rose from the waters of the sea where the winds had struck.

The first was like the lion of Ishtar, but with the wings of an eagle. The second was a bear, gnashing its teeth on the gory ribs of its latest kill. The third was a leopard with the wings of a bird; and the fourth—Daniel’s tongue cleaved to the roof of his mouth in terror at the sight of it. This creature from a twisted nightmare was utterly indescribable; its horrific appearance sent the mind reeling in revulsion. The only features that his recoiling senses recorded were its  brutal teeth of iron, with which it mauled and crushed its victims—and the ten horns on its head …

brutal teeth of iron, with which it mauled and crushed its victims—and the ten horns on its head …

Long minutes or hours later he awoke, the echo of his awesome Guide’s voice still reverberating in his mind. His heart jolted against his windpipe as the dream crossed and recrossed the window of his mind. Four beasts. Ten horns. There had been an eleventh one too, a blasphemous horn, swelling and boasting. And a glorious Son of Man, whose authority would be absolute, whose kingdom would never end … Searching within himself for a response to the fantastic mind-journey of the night, Daniel discovered two emotions intimately entwined in his soul.

On one hand he felt exhilaration. He had tasted the power of the Eternal thrumming in his vitals—for there was no doubting the Source of the vision he had seen.

On the other hand he felt a haggard sense of foreboding. It seemed the Eternal still had a calling for His world-weary servant, and Daniel knew there was no way of predicting the paths on which such a summons might place his fatigued old feet. Some tale was yet to be told, he sensed, some vision yet to be imparted.

With deliberate slowness, Daniel rose from his couch and began gathering his writing materials.

This chapter is from the novel Daniel: The Man Who Saw Tomorrow, by Thom Lemmons. The entire novel is now available for your smart phone, tablet, or other e-reading device at HomingPigeonPublishing.com. Please visit the site to purchase this book and also for more information on other books by Thom Lemmons.