PRINCE KURASH STOOD BESIDE the tenant farmer’s field, near the place where the qanatsurfaced, bringing life-giving water from springs in the faraway mountains. Again he pulled in his faraway thoughts, trying valiantly to listen carefully to the old man’s rambling complaint.

“And so you see, my prince, that my crops cannot thrive as in the past, as long as those thieves farther up the qanat steal more water than they need. I know my levies have been less of late, but I hope you will tell your gracious father, the king—may the fravashi preserve him—that my loyalty and my skill are as great as ever, but I cannot feed my herds dust, which is all I shall have in a few years if those dog-sons up the qanat don’t change their sorry ways … ”

An impressively tall man now and fully bearded, Kurash nodded thoughtfully, even as his awareness resumed its prodigal wanderings, following the direction of his gaze toward the far horizon.

He realized presently that the old farmer’s voice had stopped. His eyes met those of the farmer, who waited, plainly expecting some answer to his grievance. Kurash rubbed his beard, studying the craggy, windworn face of this man of the earth. Presently he turned to his bodyguard. “Gobhruz, have you made note of this man’s predicament?”

“I have, my prince,” answered the older man dutifully.

“Very well,” the young lord pronounced decisively. Turning away from the farmer, he swung himself up into his saddle. Looking down upon his subject with what he hoped was a benevolent, wise smile, he said, “Ulaig, your problem will be brought before the king. Justice will be done.”

The farmer turned away, apparently satisfied for now—or,if not, afraid to say more.

Kurash and Gobhruz reined their horses away from the place, the prince sighing pensively.

“Do these squabbles among the people never end, Gobhruz?” he complained as they rode away. “Is this all a king has to do: arbitrate controversies over water rights, stolen goats, and whether the horse was lame before or after the trade?”

“My prince,” shrugged Gobhruz, “the affairs of state are beyond me. But I have observed,” he continued, “that a ruler who spends more of his time assuring full bellies for his people usually spends less of his time protecting his neck.”

Kurash glanced sidelong at his mentor, grinning from ear to ear. “So the affairs of state are beyond you, are they?” Gobhruz again shrugged, the tiny smile on his lips hidden by his great bush of graying beard.

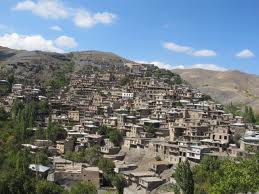

They rode into the outskirts of Parsagard, yard fowl and dogs scattering before the hooves of their horses. Those who chanced to glance up long enough to see the prince passing made the small, deferential bow of respect. Kurash had long since become inured to the display; not since childhood had he felt the small tingle of pride when his elders bowed before him.

“Don’t you find it odd, Gobhruz,” Kurash asked as the horses slowed to a short, choppy trot, “that Parsagard, the capital city of the Parsis, has no walls? The Medes erected great walls around Ecbatana and Shushan—not to mention the huge, thick walls that the Chaldeans built around Babylon and the cities of the plain. I have heard it said,” he continued, “that two teams of horses can be driven abreast along the top of Babylon’s walls! Can you imagine such a thing, Gobhruz?”

“The mountains of Parsis are our walls, my prince,” replied Gobhruz after some thought. “When the Medes began to enter greatly into the affairs of the world, only then did they begin to build walls. That is what greed does to a people—creates the need for walls.”

“You speak harshly of your own kin,” observed the princequietly.

“Aye,” nodded Gobhruz. “That is why for these many years I have cast my lot with your father and the clans of the Parsis, why I chose to live in Parsagard—the Camp of the Parsis. The tongues of the Medes and Persians may be much the same, but their hearts are not. As long as our peoples wandered together—with the sky of the world as our roof, its grasses our carpet—the need for armies and taxes was not so great. A man with a sound-winded horse was rich. An antelope taken in the chase was a banquet.

“But then,” mused the older man as the horses walked through the streets of Parsagard, their hooves kicking up dry spurts of dust in the late summer morning, “the Medes settled in the plain, beside the rivers of Elam. Their eyes began to desire more—and then more still.”

Gobhruz’s voice fell silent as they reached the stable. The two men dismounted, handing their reins to the attendants who rushed to serve them. Walking along the path toward the gable-roofed house of the king, Gobhruz mumbled, more to himself than to Kurash, “Uvakhshatra learned well from the Chaldeans. To build, and to burn. To fortify, and to hoard. To write down what is said so that one need not face his opponent, need not remember a man’s face nor the sound of his words—only the dry mud-tracks of the words themselves. Uvakhshatra learned well, indeed. His son Asturagash has inherited all his father’s greed, but none of his imagination.”

Suddenly Gobhruz stopped walking and glared hard at the prince. “Thus it is with those who build empires,” he growled into Kurash’s startled eyes. “No matter how grand, how noble the original dream, rarely does it outlive the son of the dreamer. Kings are but men, my prince—mark it well.”

Scowling at the ground, thinking he had perhaps said too much, the Medean pushed open the heavy wood-plank door of the great hall of Parsagard. Kurash stared thoughtfully at the lowered head of his servant and friend. Then he stepped acrossthe threshold into the house of his father, the king.

Kanbujiya sat upon the throne of his hall—or, rather, within the throne, as if it were a chalice to gather and hold his frail, wasting body. The aged ruler’s life flickered like a candle guttering in a breeze. Sometimes Kurash believed his father’s face was becoming transparent, as if he might eventually disappear. The frail carpet of flesh covering his tired old bones grew more and more worn and threadbare, though the eyes of the ruler of Anshan were as keen and piercing as ever. Kurash approached and knelt, kissing the hand of his father.

“My son,” came the tired, husky voice, “what will you do now?”

Kurash tilted his head quizzically toward Kanbujiya’s wrinkled face, the king’ s clear amber eyes lancing him with a query he did not understand. “What do you wish me to do, my lord?” the son asked. “I have just come from inspecting the fields and hearing the petitions of your faithful subjects. If you wish,” Kurash went on, “1 will present the cases for your judgment. Or, if the king is too tired, I will—”

With a feeble wave of his hand and a turning of his head, Kanbujiya cut short his son’s speech. With his eyes closed and his head leaning against the back of the throne, Kanbujiya wheezed, “It is far too late in the day to waste breath on humoring a dying old man, my son.”

“Father!” protested Kurash. “Do not speak so! Let me get something for you.”

“No,” whispered the king. “Nothing you can bring will benefit me now, boy.” Kurash winced at the last word, but said nothing.

“I know you have been rendering judgments in my name for several months,” continued Kanbujiya, his breath coming in shallow, jagged draughts. “What else is to be done, when the king must use all his strength to hold his head upright?”

“No, Father—”

“But what will you do, my son,” Kanbujiya persisted, againlocking his son’s eyes with that stem gaze, so disturbing for its unexpected strength, “when your time soon comes to sit in this seat and command in your own name? What will become of this valley of Anshan? What will happen to the peaceful way we have lived for the years of my stewardship?” As the eyes of his father bored in on him, Kurash dropped his head upon his chest.

“I know what courses in your blood, boy,” said the dying king. “I know how poorly tranquility sets with you. And I know, as surely as I hear the beating wings of the fravashi who come to bear me to the Undying Flame, that you dream of glory, and of power, and of conquest. This valley of Anshan can no more contain your ambition than a wicker basket can hold live coals. I have seen it in your face since the day they brought you to me for naming.”

For several moments the only sound in the hall was the ragged sound of the old man’s breathing. Then he roused himself once more. “Kurash—‘Shepherd’—is what you are called, my son. Never forget that you are the shepherd of this flock, this house, this land. Be careful where you lead them. Be careful of other pastures, other herds. Be careful … ”

A long silence followed, punctuated by the distant, outside sounds of children, birds, dogs—of life in Parsagard. When at last he could raise his eyes, Kurash looked again at the face of his father.

The keen eyes of the king were fixed in an unblinking stare toward the raftered ceiling, a glassy, translucent sheen gathering slowly on their drying amber surfaces. Kurash knew. Tenderly he reached up and pressed his father’s eyelids closed. Turning to Gobhruz, kneeling silently by the door through which they had entered, he said in the tongue of his homeland, “Shah mat—the king is dead.”

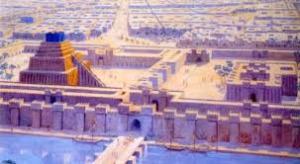

IT WAS THE WEEK of the New Year Festival in Babylon, and the streets of the capital thrummed with the frenetic jubilation of her two hundred thousand residents as they celebrated themost important high day of the year. Many merchants’ shops were closed in observance of the feast. Young sons of noblemen and wealthy merchants, emancipated from the strict lessons of their tutors, ran giddy beside the canals and along the avenues, drunk on the freedom that accompanied the celebration. Even the riverside Karum district—its docks, quays, and exchanges usually bustling with commerce until late at night—was largely abandoned during these days. In the month of Nisan, as the sun crossed the midpoint of his journey back from his southern winter quarters, Babylon gave herself wholly to celebrating Marduk’s homecoming.

Today was the climactic day of the festival. With great pomp and ceremony, the image of Marduk would parade down the Processional Way, from the Temple of the New Year Festival just outside the Ishtar Gate to the huge temple complex of Esagila. For several days now the god had been sequestered outside the walls of the city in the closely guarded temple, as secret rites were performed to consecrate the city and thank Marduk, Lord of the Sun, for his rebirth and return. Today, with fanfare and flourish, the glittering image, dressed in regal purple linens and resplendent with flower garlands, would proceed along Aibur Shabu while the people showered their praises and adoration upon him. His palanquin would be heaped with grain offerings and the choicest fruits, and a host of brilliantly clad priests would solemnly accompany him to his sanctuary in Esagila.

But this was not the end. Once Marduk was ensconced in his seat of power, the emperor, dressed in the drab costume of a supplicant, would come out of his palace, humbly traveling afoot—with no crown, no gold-threaded linens, no gaudy display of rank or power. The crowds along the way would watch in somber, hushed reverence, in stark contrast to the earlier loud celebration for the passing of Marduk. With only a handful of bodyguards surrounding him, Nebuchadrezzar would make his annual pilgrimage, tracing the god’s route along Aibur Shabu to the judgment seat of Marduk. Here he wouldprostrate himself before the Father of All, as was proper for the earthly regent of Marduk.

After making the prescribed obeisance and taking part in the sacrifice of a sacred white bull, Nebuchadrezzar would grasp the outstretched hands of the god, and a representative of Marduk would bestow upon the god’s earthly prince a scepter, the badge of his favor and authority.

Having thus received his charter to rule for another year, Nebuchadrezzar would throw off his drab cloak to reveal beneath it the splendor befitting the chosen regent of Marduk. A crown of gold would be placed on his head, and a torque of silver about his neck.

By then the late evening shadows would be falling across the broad boulevards of the capital city, but not a soul would stir toward home. They would be crammed as a solid mass into the huge plazas of Esagila and along every approach to the temple complex. Breathlessly, all Babylon would watch as the emperor, no longer displayed as supplicant of Marduk but as his earthly manifestation, passed the portal of the god-house and promenaded toward the ziggurat of Etemenanki, the Foundation of Heaven and Earth. He would ascend the steps to the very topmost platform. To the gaping masses the emperor seemed to climb, like a glittering god, to the roof of heaven itself. There, perhaps two hundred dizzying cubits above the heads of the eagerly waiting masses, Nebuchadrezzar would raise the scepter in a salute to the setting autumn sun. This was the signal for the revelry to begin in earnest.

IN THE DECLINING SUNLIGHT outside the city walls, beneath a grove of palm trees on the river’s eastern bank, a few dozen devout Hebrews gathered in a small huddle. This sunset would also mark the day of shabbat, although scant few inside the walls of the city would have known or cared. These few under the palm trees did know and care, however, and chose to be here rather than partaking in the merrymaking of the NewYear Festival.

A few groups like this one were now clustered in other meeting places—beside a remote stretch of canal, or at an unfrequented section of the riverbank. The Hebrew faithful sought such unobtrusive places for their weekly gatherings because of the unofficial censure and private rancor of much of Babylon’s populace. No one, however, dared open hostility toward the Jews; the emperor’s edict in favor of the odd religion of Vizier Belteshazzar and his fireproof friends had been in place for almost a score of years.

Despite the resentful mutterings toward the Jews of Babylon, many of them clung tenaciously to these weekly gatherings as the only available means to retain a grip on their identity. The destruction of Jerusalem and the Temple had caused a profound shift in the way these Chosen Ones saw themselves and their God.

How was it possible, they asked, that the covenant God made with Abraham and Jacob, and reiterated to David and Solomon, could be so disastrously and completely revoked? That the Holy One could prove false was unthinkable. Therefore the fault must lie within His people.

This line of reasoning spurred them into meticulous compilation and assiduous study of the Books of the Law and the Prophets. The warnings and pleadings of Isaiah and Jeremiah came to have a retrospective meaning they had never before apprehended. The codes handed down during the Exodus gradually became the measure of faith and practice for a generation of exiles learning to see with new eyes.

As the glowing disc of the sun touched the featureless rim of the western horizon, the middle-aged Levite who presided over this assembly rose to his feet before the group. With eyes closed, swaying to the rhythm of the ancient language of Judah, he led the congregation in the singing of the Shema:

Hear, O Israel:

The Lord our God, the Lord is One.

And thou shalt love the Lord thy God

with all thy heart,

and all thy soul,

and all thy strength,

and all thy mind …

As the last tones of the age-old hymn faded in the gloaming, the teacher took up a scroll. Unrolling it to the place he sought, he began reading.

All who make idols are nothing,

and the things they treasure are worthless.

Those who would speak up for them are blind;

they are ignorant, to their own shame …

The blacksmith takes a tool

and works it in the coals;

He shapes an idol with hammers,

he forges it with the might of his arm …

The carpenter measures with a line

and makes an outline with a marker;

He roughs it out with chisels

and marks it with compasses.

He shapes it in the form of a man,

of man in all his glory,

that it may dwell in a shrine …

Far behind him, a great shout went up from Etemenanki and its environs as Nebuchadrezzar’s ritual salute to the sinking sun released the tightly wound anticipation of Babylon’s celebrants. The heads of the teacher’s listeners shifted toward the huge sound, plainly audible even here. For a moment, just outside the walls and a world away, they pondered the vast difference between the quiet, reflective mood in the grove and the raucous, pagan spirit that possessed the vast majority of the empire’s citizens on this day. Then their eyes returned to the reader’s lips as he went on:

Half of the wood he burns in the fire;

over it he prepares his meal.

He roasts his meat and eats his fill.

He also warms himself and says,

“Ah! I am warm; I see the fire.”

From the rest he makes a god, his idol.

He bows down to it and worships,

He prays to it and says,

“Save me—you are my god.”

They know nothing, they understand nothing.

Their eyes are plastered over so they cannot see,

and their minds closed so they cannot understand …

Remember these things, O Jacob,

for you are My servant, O Israel!

I have made you; you are My servant.

O, Israel, I will not forget you.

I have swept away your offenses like a cloud,

your sins like the morning mist.

Return to Me, for I have redeemed you …

Carefully the teacher placed the scroll aside, his eyes lowered in reflection for several heartbeats before he faced his audience. “On this day of all days, my brothers, these words of the blessed prophet Isaiah should remind us that we dwell here, like latter-day sons of Moses, as strangers in a strange land. This place is not our place, and it was not for nothing that the Eternal called our most ancient father Abraham out of this same land, with its false gods and innumerable idols.

“Remember the Lord, my people,” he said, his eyes punctuating his words with quiet fervor. “Do not forsake His ways. Keep yourselves according to the covenant He gave us at Mount Sinai. Because our kings and people broke faith with Him when we lived in Judah, He has allowed these calamities to befall us; we are captives here because of the iniquity of the past.

“But the past is not the present, nor the future,” thepreacher insisted, a faint hope blushing in his cheeks. “The Almighty One is faithful, and He will remember His people. We, for our part, must be faithful to Him.”

The rabbi sat down, inviting comment or discussion of the reading. In the lull, the sounds of flutes and tabors, of clapping hands and dancing floated above the walls of the city and down to them on the wind.

One of the younger men rose to speak. “What you say is true, Ezra ben-Seraiah. The people of this place, even its king, do not revere the One. My employer, Jacob the son of Uriah, whose people once knew the Lord—even he does not do righteousness. Babylon has turned aside Jacob’s face from the Lord, just as Babylon seeks to do to us all—just as it has done to people of all places for ages beyond remembering. Why then, Teacher, must we continue to pray for the welfare of this place?” The speaker looked about him for support, and saw several heads nodding. Even beyond, in the circle of women and children who sat apart, yet within hearing, his words found acceptance.

He went on: “Like you, Brother Ezra, I am of the tribe and lineage of Levi. I was born in Babylon, and my son is now almost old enough to receive the Law. From the time I can remember anything, I have gathered with the faithful, shabbat after shabbat, to hear the Law and receive its instruction. Is this all my son may look forward to—an uneasy truce with a king and people who do not know the Living God? How long must we wait for the fulfillment of the word of the Lord, according to His servant Jeremiah? When will the time of return come?”

The young man sat down, having aggravated in each heart present the constant, unspoken question pondered by every Jew in Babylon: Will it be too late? Will we, or our children’s children, be subsumed by the dragging, ever-present seduction of the glittering culture surrounding us? When the Lord calls, will anyone still desire to listen?

Ezra stared at the ground, unable to frame the words for a reply. How many times had he asked himself the same thing?How often had he felt the pull, the desire to surrender to the easy blandishments of life within the majority? His own unease tied his tongue, preventing him from giving the quick denial he knew his listeners wanted to hear.

He heard the rustle of robes—someone else standing to speak. Raising his eyes, he saw Daniel looking carefully around the circle of faces. A deeper silence fell as the respected, powerful noble gathered his thoughts.

“Brother Jozadak,” he began, addressing the man who had just spoken, “you have well said that this kingdom and its king do not worship the Lord. Who can know this better than I?” This was accepted silently, each hearer rehearsing his own memories of the career of Daniel-Belteshazzar—interpreter of dreams and confidant of the emperor. Sometimes quietly, often openly, he had interceded on behalf of the people of Israel. What Hebrew did not rest easier at night knowing Daniel sat at Nebuchadrezzar’s right hand?

Daniel, for his part, had other memories: of the abandonment of friends and the embracing of falsehood … of the rapping of a beggar’s cane, and an inward, certain choosing … of the sickly sweet taste of a lie, and the nausea of guilt. As recently as today, he had fought the old fight with fear—it was not an easy thing for such a highly ranked one as himself to be absent from the New Year Festival.

Taking a deep breath, Daniel went on. “And yet, I believe Adonai has a purpose for this place—perhaps even a love for its people.”

Jozadak’s expression plainly advertised his skepticism.

“Don’t you see, my brothers and sisters?” Daniel asked, his arms spread wide, taking them all within his embrace. “He is the Creator of the whole world, of every living thing, every rock and river. Marduk did not build Babylon! Nabu didn’t trace the path for the Tigris and Euphrates! The One God, El Shaddai—it is He who has made this and all other places, and who has brought His people here for a season, for purposes of His own.”

A few more faces seemed to be listening, turning over these words, strange-sounding though they were.

“Don’t you remember,” said Daniel, leaning firmly into his plea, “what was spoken by the Lord through the blessed prophet Jeremiah? ‘I made the earth and its people and the animals that are on it, and I give it to anyone I please. Now I will hand all your countries over to My servant, Nebuchadrezzar … ’” Daniel allowed the last three words to hang in the air, allowed the silence to shout it in their ears again and again: My servant, Nebuchadrezzar …

“A time is coming, my people,” said Daniel, “when God shall kindle a light to be seen by all the nations.” Something ignited in his voice with those words; a deep, strong radiance spread within him, wafted him upward, giving bright tongue to a beacon-glow better known by the heart than the eyes. “He shall draw unto himself a holy people called out from every tribe and tongue under heaven,” intoned Daniel, his voice like a father’s comfort. “And every king, every prince, every power shall serve Him, just as this very day the emperor of Babylon serves Adonai’s purpose, though he knows it not.”

A few heartbeats longer Daniel stood, staring avidly up through the gently swaying leaves of the palm trees, wrapped deep within the potency of his vision. He remembered the turbulence of words he had uttered on another day, a day when a young man stood in the court of the emperor and spoke of things taught him by a Source beyond. Has it really been so long ago? he wondered. Passing a hand over his eyes, he sat down.

A reflective silence softly enfolded the congregation beneath the palms. As the last gold-and-rose streaks of evening ebbed past the threshold of the west, Ezra picked up his scroll and read softly Isaiah’s comforting words of Judah’s future, with their mysterious reference to a chosen one called “Kurus” in the Hebrew tongue:

“I am the Lord,

who has made all things,

who alone stretched out the heavens,

who spread the earth out by Myself …

who says of Jerusalem, “It shall be inhabited,”

of the towns of Judah, “They shall be built,”

and of their ruins, “I will restore them … ”

who says of Kurus, “He is My shepherd,

and will accomplish all that I please … ’”

This chapter is from the novel Daniel: The Man Who Saw Tomorrow, by Thom Lemmons. It will soon be available for your smart phone, tablet, or other e-reading device at HomingPigeonPublishing.com. Please visit the site for more information on other books by Thom Lemmons